St. Julien, Raised Far From the Track

Joseph Sayer Dunning loved horses.

They were part of the daily grammar of his life — harnessed, fed, trusted. He knew how they moved when no one was watching. How they behaved in the dark. How they worked when there was something real to pull.

Joseph, my 3rd great-grandfather, was born March 9, 1833, in Orange County, New York, the eldest son of Virgil and Eliza Sayer Dunning. His father ran a large farm, and Joseph grew into the work early. He was, according to his obituary, “generously educated at home and abroad,” a phrase hinting at his curiosity.

In 1859, when he was 26, Joseph married 22-year-old Clara A. Owen. Two years later, with the start of the Civil War, he enlisted as a private in the 6th New York Infantry Regiment — Billy Wilson’s Zouaves. He served two years, mustered out with his company, and returned — again — to the land.

After the war, life in Orange County returned to its familiar rhythms of work. Dirt roads connected farms. Rail lines carried milk, produce, and livestock to New York City. Middletown and Goshen anchored the region, but beyond them, life followed the demands of chores and daylight. Horses mattered here not as spectacle, but as necessity. They hauled milk to the depot, pulled wagons to market, and moved goods that had to arrive on time.

It was also a place that knew horses. For decades, Orange County had been one of the country’s steady sources of trotting stock, shaped by pasture, water, and use. By the late 1860s, Joseph and his brother Benjamin were breeding horses on their farm between Denton and Middletown. It was work done alongside the other demands of the farm.

In 1869, a bay gelding was foaled there — sired by Volunteer, a son of Rysdyk’s Hambletonian, the foundation sire of American trotting horses. The dam was Flora, a mare whose lineage suggested speed. On paper, the colt carried strong blood. In practice, he was simply another young horse expected to work.

In time, he would be known as St. Julien.

The name did not originate in the barn or the field. It arrived later, after the horse left Joseph Dunning’s hands, acquired by owners who saw in him not a worker but a phenomenon. According to later accounts, James Galway — the veteran New York turfman who purchased the horse — named him after spotting the name on a bottle of wine. Such a detail fits the moment: a rural workhorse stepping suddenly into a world of polish, money, and display.

But before the name, there was the work.

St. Julien and his full brother, St. Remo, were worked together as colts. They pulled wagons. They hauled produce. They delivered milk to the railroad station — a daily route that demanded calm, consistency, and obedience. According to a contemporary account in The New York Sun, it was likely a milk wagon that St. Julien pulled the very first time he was put to harness.

A friend of Joseph Dunning later recalled driving the team himself, sometimes on nights so dark the horse was invisible in front of him. He never shied. Never broke gait. Never paced or skipped. He trotted square and level, straight down the road, as if the darkness were irrelevant.

“He was more like an old mare,” the friend said, “steady and reliable.”

He never showed the least inclination to move any other way. Trotting was simply how he went down the road.

Joseph Dunning didn’t recognize — or perhaps just didn’t pursue — the colt’s extraordinary potential. He sold the horse for $600 to Galway, a man with a sharper eye for opportunity. Galway later sold the horse west, where he came into the hands of Orrin A. Hickok, a skilled trainer and driver who understood what he’d been given.

An 1880 color lithograph by William Harring, published in San Francisco and preserved today in the Smithsonian, shows St. Julien at rest, far from the track.

Under Hickok, St. Julien entered the trotting world like a revelation.

He didn’t debut until he was 7 — an unusually late start — but when he did, he won everything. Six races. All first money. Every heat straight. No hitches. No missteps. No theatrics. He raced with mechanical precision, newspapers said — a steadiness learned long before the track.

By 1879, St. Julien was the world’s champion trotter. In Oakland, California, he lowered the mile record to 2:12¾, a time that reset expectations for what a harness horse could do. Newspapers across the country took notice, and St. Julien’s reputation traveled faster than the trains that carried him from meet to meet.

Two years later, at the Gentleman’s Driving Park — a Victorian-era harness racing track on Long Island — he appeared before one of the most fashionable sporting crowds of the era. More than 8,000 spectators filled the grandstand and clubhouse balconies, spilling onto the bluff and down to the track. Wall Street financiers and prominent breeders stood alongside politicians and generals. During the first heat, Ulysses S. Grant watched from the judges’ stand, later crossing the track to the clubhouse, where he was recognized by the crowd and received an ovation.

St. Julien didn’t disappoint. He defeated Trinket in three straight heats, confirming his status not just as a record-holder, but as the dominant trotter of his generation.

As his fame spread, St. Julien crossed from sport into image. Currier & Ives immortalized him in hand-colored lithographs, capturing the horse at full extension, hooves suspended midstride. In parlors and offices across the country, St. Julien became something to hang on a wall: speed rendered permanent, effort transformed into art.

Through it all, Joseph Sayer Dunning stayed home.

He bred other horses — St. Elmo, Prince (later called “Joe Dunning”) — but none reached St. Julien’s renown. His farm in Wawayanda became known as “a model of efficiency and hygiene.” He read deeply. He followed national affairs. He served the First Presbyterian Church of Middletown. He raised three children — including Flora Nurt Dunning, my 2nd great-grandmother — who would carry the family line forward.

In a county that knew both the pride and the excess of the trotting turf, not every horseman felt compelled to follow a horse to the grandstand.

Joseph never trained a horse for the track. He never stood in a grandstand. He never saw St. Julien race. These facts appears in his obituary without judgment, almost without curiosity — as if it made perfect sense.

When Joseph Dunning died in 1918, the horse that had carried his legacy into history had already been gone for nearly a quarter century. St. Julien retired to a horse farm and died in 1894 at age 25 after going missing for several days.

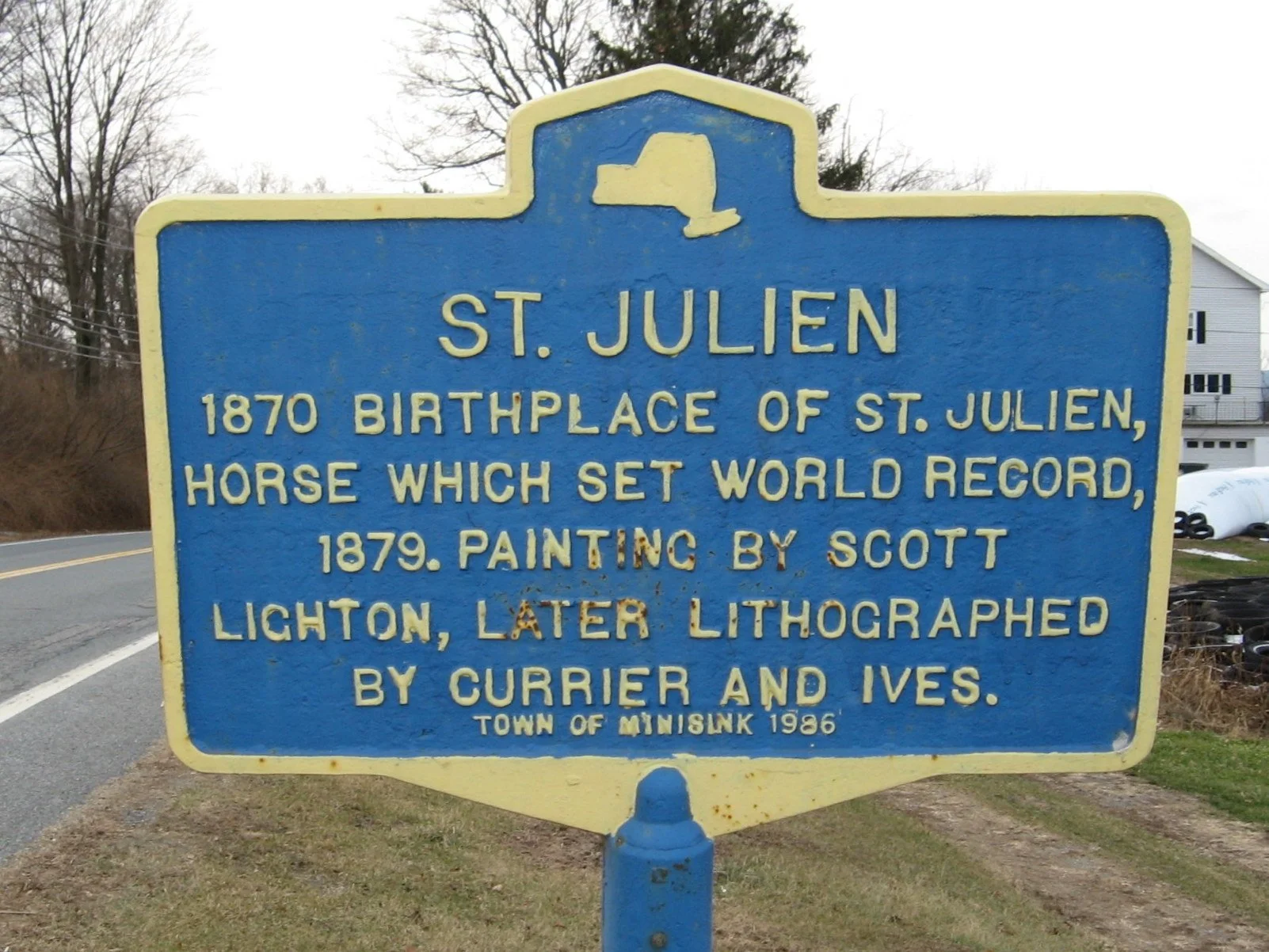

In 1986, a historical marker was erected in Orange County to commemorate St. Julien’s birthplace. It notes the world record. It notes the famous Currier & Ives print. It stands near the intersection of Route 284 and Farms Road.

It doesn’t mention the milk wagon. Or Joseph Sayer Dunning.

A historical marker in Westtown, New York, noting the birthplace of St. Julien, was erected in 1986.