The Whale and His Birthday

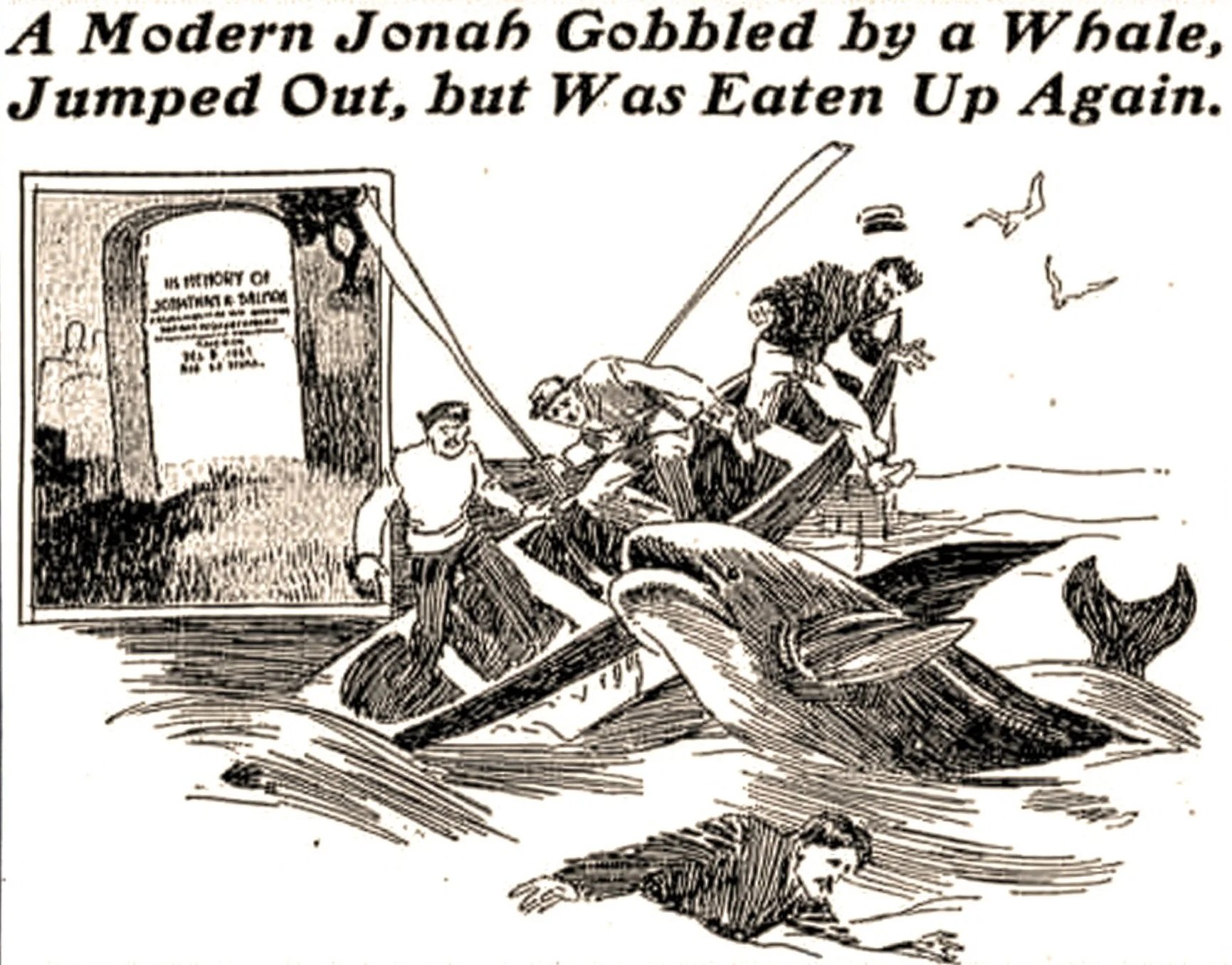

An illustration from the Jan. 31, 1904, Chicago Sunday Tribune marking the death of James Brewster Salmon depicts the death of his brother Jonathan Horton Salmon half a decade earlier in the South Atlantic.

The whale rose first as a shadow.

In the flat blue water of the South Atlantic, the six men in the whaleboat would have seen only the surface disturbance at the start — a dark swivel of motion that violated the calm. The sea there, at 38°40' south latitude and 34° west longitude, can look like hammered blue metal when the sun is high, far from any land and blank enough to unsettle. A place without a single landmark, without even the comfort of a seabird, where distance collapses and the horizon feels too thin to hold.

We know those numbers only because someone wrote them down. In the Arabella’s logbook — a thick, salt-stained volume kept by First Mate James Hodgdon from Aug. 11, 1847, to July 9, 1849 — the position appears without comment. Just coordinates. A date. Weather. Routine. And, on one line, a death.

Before anyone shouted that morning, before the oarsmen braced, the whale’s back broke the surface with a slow, deliberate roll, the way a mountain might reveal itself if it decided, suddenly, to move. A hulking shape under the water. A glossy sheen above it. The men tightened their grip on the ash oars, and the second mate — a young man from Honesdale, Pennsylvania — crouched forward near the bow, eyes locked on the boatsteerer’s shoulder.

The harpooner hurled his lance.

What happened next would be told and retold in fragments: a stunned gasp, a fluke cutting the air, a blow that felt like the sky itself striking down. But in this moment — the moment before the worst — everything was astonishingly quiet. Just the creak of the boat. The hiss of the harpoon line drawing tight. The steady, indifferent breathing of the sea.

Out here, the ocean doesn’t care whether a man is brave or young or beloved. It does not care that it is his birthday. It does not care that he has a family waiting in a river valley thousands of miles away.

It moves. And men move inside it.

The tail rose out of the water like a giant’s arm. And then the boat — the whole boat — lifted.

The sea’s violence has always had a strange echo in the hills of northeastern Pennsylvania, a place built on coal seams and river bends, where the highest drama is usually weather or work, not whales. Yet it was from here, in the 1830s and 1840s, that the Salmon family learned to navigate both kinds of danger: the sudden, savage kind — like a boat shattered by an enraged whale — and the slow, creeping kind that moves through a family quietly, rearranging it year by year.

Honesdale was not yet 50 years old when the Salmons arrived from Bloomingburg, New York, about 60 miles east. It was a town of just 60 families and a little over 106 souls — a scattering of houses along a new canal, where coal cars groaned down the gravity railroad and hemlock forests pressed in on every side. It was a place shaped by movement. Risk shaped it, too. For a boy growing up here, the sound of leaving was as common as the sound of work.

Back then it was still more frontier than town. The Delaware & Hudson Canal had carved a watery corridor through the valley, bringing with it the clang of lock gates and the stink of mule sweat. Canal boats drifted past the docks like sluggish animals, delivering anthracite coal to Kingston, then to the markets farther down the Hudson.

On warm days, the banks of the Lackawaxen River smelled of sawdust and fish. On cold ones, woodsmoke settled into the low streets. A traveler approaching town from the east would have seen the steeples first, pale against the hills; then the brick storefronts and boardwalks; then the clustered houses rising toward the ridge where Irving Cliff, named for the writer Washington Irving who once visited and was said to admire the view, kept watch. At night, lamps flickered through lace curtains. The town glowed as if trying to convince itself it was sturdy.

For Benoni and Susan Salmon, raising eight children here meant both opportunity and risk. After the War of 1812, Benoni’s life seems to have been one of steady work — militiaman, farmer, father — though the records blur and contradict in the way 19th century documents often do. His children were born in Bloomingburg and Blooming Grove before the move to Honesdale, and they brought with them the habits of a small, tight-knit Protestant household: morning chores, evening prayers, the discipline of many hands sharing one table.

And then there were the noises — ones that shaped a child’s early memory: the cold slap of Dyberry Creek after rain, the crack of a blacksmith’s hammer near Main Street, the squeal of wagon axles protesting under heavy loads, the calls of canal hands guiding their teams along the towpath. Honesdale was a place where industry and wilderness pressed against each other, neither quite winning.

Jonathan Horton Salmon grew up in this noise. So did his brothers Charles and James. And if you were to imagine the three of them in those years, you might begin with nothing dramatic: boys skipping stones near the river, running errands for their father, carrying tin lunch pails past the canal locks.

Jonathan was the third-born and the oldest son, the one the others watched. James came two years behind him, the brother who would one day be 20 feet away when the sea took Jonathan.

Charles was quieter, steadier — the boy who preferred gears and schedules, who would become a railroad conductor and learn timetables like scripture. He would be my third great-grandfather.

Their sisters rounded out the house: Hannah, the oldest sibling, methodical and kind; Lurana, who would live into the new century; Elisabeth, who drifted west to Missouri; Maria, who died young with her child; and Mary Amanda, lost at 14. Ten in all, a family bending and reshaping itself around every arrival and absence.

It was the kind of house that always had a draft, a Bible open on a table, a quilt half-finished in someone’s lap. The kind of house where news arrived by letter or horse or not at all. And it was from this house, in a town barely on the map, that two brothers decided to follow the pull of the sea.

Long before anyone carved his name into stone or read his death aloud in a Pennsylvania newspaper, Jonathan Salmon was simply one of the eight children Benoni and Susan were trying to raise in a world that didn’t yet know their names.

He was born Dec. 8, 1819, in Bloomingburg, New York — a village of clapboard houses, Dutch church bells, and the long, slow rise of cattle-dotted hills. His parents had married young, survived Benoni’s War of 1812 service, and begun building a family the way people did then — one child after another, each arrival overwhelming and ordinary.

Jonathan grew into a boy who noticed things: the pitch of the wind, the moods of animals, the way the older men talked when they thought children weren’t listening. He had his mother’s watchfulness and his father’s broad-shouldered steadiness, though the steadiness never sat quite as firmly on him as it did on his younger brother Charles, who came along five years later.

Charles Milton Salmon was the one who kept his shirt tucked, who finished chores without being asked, who seemed born knowing how to smooth tension out of a room. If Jonathan sparked, Charles tempered. If Jonathan’s eyes pointed down some imagined road, Charles’s pointed home.

And in between them was James Brewster Salmon, quieter, more easily led — the brother who tagged along.

Eight children under one roof meant noise, laundry, scraped knees, and a constant search for enough money. It meant faith, routine, and discipline. It meant responsibility learned before adulthood.

For Jonathan, it also meant restlessness. For Charles, loyalty.

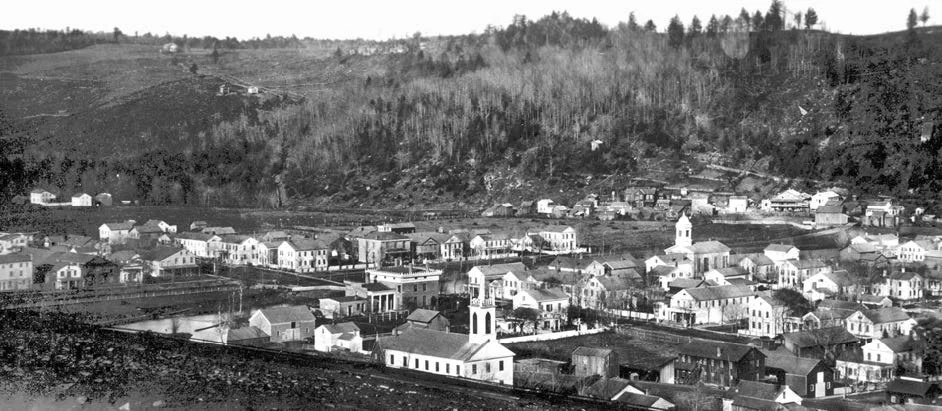

Taken around 1860, this northeastward view of Honesdale reveals how the bustling commercial center of “Lower Honesdale” grew faster than the quieter, more residential “Upper Honesdale” beyond the Lackawaxen River.

Around 1830, when Jonathan was 11 and Charles still a small boy, Benoni moved his family west to Honesdale, Pennsylvania — a decision shaped by work, not wanderlust.

Honesdale was barely a town then, just a new canal cut through the forest, a scattering of houses near the confluence of the Lackawaxen River and Dyberry Creek, and the slow arrival of the anthracite trade that would define the region. The Delaware & Hudson Canal was still so new it carried a smell: wet limestone, timber, mule sweat, the black mineral tang of coal dust rising off barges.

Jonathan would have seen it all: the blacksmith’s sparks dying in the dirt, a line of mules tugging a barge past a lock, children balancing on the canal’s stone ledges, immigrant workers shouting across the water in accents thick with other countries.

If Bloomingburg had been contained, Honesdale felt larger — not in what it was but in what it promised. Strangers arrived daily. Money flowed in a way it didn’t in a farming village. Even in a valley, the world felt open.

The Salmons settled near town — not far from the rise of land that would later become Glen Dyberry Cemetery, though at that time it was all just hillside, creek, and stand of trees. They lived close enough to hear the canal traffic but far enough to see the stars.

Children grew fast in a place like that. Jonathan faster than most.

Created around 1839 by artist Orlando Hand Bears, this early view of Sag Harbor shows the bustling whaling port from the north, sweeping from Conklin’s Point in the east to the North Haven bridge and the shoreline beyond to the west.

No one knows the exact moment Jonathan decided to leave the hills for the coast, or when James chose to follow him. But the family’s Long Island roots — reaching back to their paternal grandparents in Southold and the old Puritan settlements — must have carried some influence. The Salmons came from a place where the sea was not metaphor but fact: men built ships, hunted whales, crossed oceans, and never fully let go of salt air.

Even in Honesdale, the stories traveled. And Sag Harbor was booming.

In the 1830s and ’40s, the village on the edge of eastern Long Island was a wonder of motion and ambition — ropewalks stretching for blocks, shipyards full of half-built vessels, barrels stacked like brick walls, and the smell of tar warming in the sun. Whaling crews came from everywhere: Montaukett men, Cape Verdeans, Portuguese sailors, Yankees from New England, and boys from inland who wanted something more than their father’s land would give them.

American whaling was near its peak. Ships sailed for years at a time, chasing whales from the South Atlantic to the Pacific and back, looking for three prizes: barrels of oil rendered from blubber, spermaceti for cosmetics and candles, and whalebone — baleen — to stiffen corsets and umbrella ribs. On deck, the work was brutal and technical. Below deck, it was something else entirely.

Life aboard a whaling ship meant living in a cramped, heaving society cut off from the world. The Arabella, like most ships her size, likely carried 20 or more men. The captain slept in a cabin with a sofa and real chairs. The mates had smaller cabins. Everyone else crammed into the forecastle, or fo’c’sle — a low, triangular cave under the bow where the air stayed thick with smoke, sweat, and the sour sweetness of salted meat.

A whaleman’s ration was “salt horse” — beef or pork preserved to the edge of edibility — hard biscuit, beans, rice, and molasses alive with cockroaches. Fresh food was a gift of landfall. Rats and bedbugs were facts of life. Flogging and irons were tools of discipline. Pay was not wages but a lay, a fractional share of whatever profit the voyage produced. A green hand might return after three or four years with barely enough to cover his debts at the ship’s slop chest.

And yet men kept signing on. Some out of desperation. Some for adventure. Some, like Jonathan and James, because the sea offered a chance to make a life that felt larger than the ridges around Honesdale.

Two brothers from a canal town stepped into that world.

In early August 1847, the Arabella cleared Sag Harbor. Her owners, the firm of N. & G. Howell, registered her voyage “to the Pacific.” The first pages of the ship’s logbook are full of routine observations — wind, sail, bearings. On Aug. 11, Hodgdon wrote: “Make our departure from Gardiners Point at 2 o’clock.” The handwriting is small but confident.

Jonathan was 27, seasoned enough to be trusted as second mate. The log identifies him simply as “J. Salmon.” James was 25, eager and loyal in that way younger brothers often are.

They left behind their parents, their siblings, and Charles — who was just beginning his own adult path, one that would bend toward railroad tracks, depots, and schedules instead of masts and spars.

For months, Jonathan’s life was reduced to the pace of the ship and the moods of the sea.

Days blurred: light winds, “all hands variously employed,” no whales in sight. They crossed the equator, watched the water darken, and entered latitudes that felt less like geography and more like a test of patience.

On deck, work never stopped. Men scrubbed away old blood from the last whale taken. They tarred rigging, patched sails, and spliced new rope into old. Below, they tried to sleep in narrow bunks as the hull groaned around them.

Evenings, when the weather allowed, the crew came up to breathe. They smoked, mended clothes, carved scrimshaw into whale teeth and bone — small works of art meant for sweethearts and families they wouldn’t see for years. They swapped stories of other voyages, other captains, other narrow escapes. When two whalers met, they held a gam — visiting, gossiping, trading news like freshwater.

The Arabella’s logbook, which now sits in a whaling archive far from the sea, gives almost none of that texture. It records what mattered to the ship as a machine: wind direction, sail states, positions, whales struck, oil taken, accidents and deaths. It is the voice of duty, not feeling.

And because Hodgdon, the first mate, did his duty, we can follow the Arabella south. Past the tropics. Into the cooler mid-latitudes. Toward that bare patch of chart at 38°40' S, 34° W where a right whale and a whaleboat met.

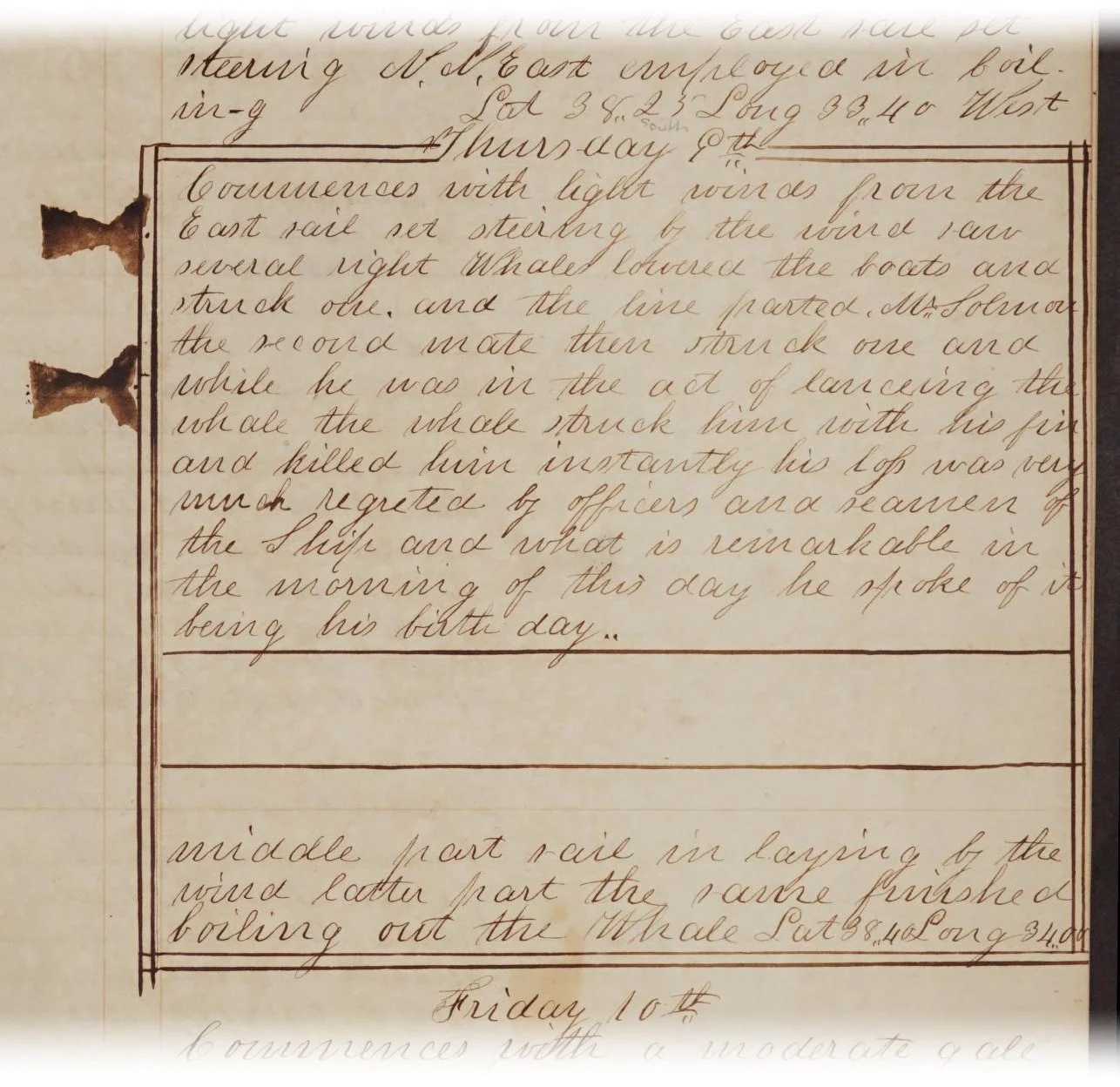

The Arabella’s logbook for 1847–49 records the moment a whale struck and killed second mate Jonathan Horton Salmon — a spare, haunting entry written by first mate James Hodgdon

We know what happened that day because two very different documents survived.

The first is the logbook itself. The hand is Hodgdon’s. The language is spare:

“Commences with light winds from the East sail set steering by the wind saw several right Whales lowered the boats and struck one, and the line parted. Mr. Salmon, the second mate then struck one and while he was in the act of lancing the whale the whale struck him with his fin and killed him instantly. His loss was much regretted by officers and seamen of the Ship and what is remarkable in the morning of this day he spoke of its being his birth day.”

That’s the whole entry. No dramatics. No description of the sea or sky. Just the essentials: the quarry, the action, the blow, the death, the fact that he had mentioned his birthday hours before he died.

The second account came later, in a letter Hodgdon sent to Honesdale, then into a story in the Wayne County Herald. That version adds human detail.

The Arabella had already taken three whales from a school near those coordinates. On Dec. 8, the boats went out again. The men lowered into the small double-ended craft that had been perfected for this job: whaleboats, narrow and fast, light enough to hoist on davits, strong enough — usually — to survive being towed at dangerous speeds behind a fleeing whale.

Right whales are huge animals, up to 50 feet long, their square heads and black backs rising from the water like moving piers. When they surface, the breath from their twin blowholes hangs in the air in a distinctive V-shaped spout. When they’re struck, they can be terrifying.

Jonathan’s boat closed on one of them. The harpooner cast. Iron found flesh.

In the first moments after a strike, a right whale might sound — diving deep and towing the boat like a runaway sleigh — or it might turn and fight. This one fought.

As later reports tell it, the fluke came down before the men could pull clear. The impact launched the boat into the air, oars and men and gear scattering across the chop. Jonathan landed closest to the whale, the worst possible place.

He grabbed his oar.

When the whale turned toward him with its great jaws open, Jonathan jammed the oar crosswise. It lodged for a moment against the hinges, keeping the mouth from closing fully. It’s the sort of detail another whaleman would notice and remember: the instinct, the strength, the refusal to let go.

He tore free and swam for the second boat. James was in it, pulling hard. They dragged Jonathan aboard — soaked, shaken, alive.

The logbook doesn’t mention any of that. It doesn’t need to. The ship’s record keeps no tally of miracles.

But the letter does, right before yanking it away.

As the second boat tried to haul men from the wreckage, the whale came again. A right whale’s tail can weigh as much as a small boat. It rose, arced, and came down.

This time, the strike shattered the rescue boat. Men tumbled. The water went white.

Jonathan hit the sea again. There was no oar in his hands now, no second reprieve.

Witnesses said the whale’s fin — or its great head and jaw — struck him as he surfaced near the chaos. “He was instantly killed,” Hodgdon wrote. “We could not obtain his body. It sunk beneath the surface of the waters and we never saw it more.”

He died on Dec. 8, 1847. He died on his 28th birthday.

News in 1847 moved like an old horse — slow, uneven, subject to weather and chance. A death in the South Atlantic might take months to reach the hills of Pennsylvania, and longer still to settle in.

Charles Milton Salmon — then 23, newly married to Jeannette “Nettie” Russell that past September — learned his brother was gone the way people learned everything then: by letter.

Charles and Nettie had married in Tunkhannock, the Russells’ Pennsylvania home. She was a schoolteacher, steady and intelligent, the daughter of Vermonters who had moved west when she was a girl. During their early married life, they lived in places that echoed the Salmons’ own migrations: Honesdale, Susquehanna Depot. Charles worked as a tinsmith for a time, then, in his late twenties, as a railroad conductor — riding iron rails instead of ocean swells.

They were just beginning to settle into their small routines — rented rooms, shared meals, the early conversations couples have about where they might live next — when Hodgdon’s letter arrived.

It would have come folded sharply, addressed in the careful hand of a man who knew bad news had weight. Charles was not yet the well-known Erie Railroad conductor he would become, the man whose name would appear in obituaries describing him as “one of the oldest and best-known conductors” on the line. He was young, a husband of only a few months, trying to build a life that looked forward, not back.

And then his brother was gone. And soon after, his 14-year-old sister Mary Amanda would die too.

Pain arrived quickly in those years. But Charles was the quiet, loyal kind. He carried this sort of news carefully, didn’t turn his grief outward more than necessary.

He walked the letter to the office of the Wayne County Herald, where the editor copied it down and printed it on Mar. 22, 1848, so the town could understand what had happened and the family wouldn’t have to retell it to every person who asked.

When someone you love dies at sea, the story is all you get.

Honesdale’s Glen Dyberry Cemetery in the late 19th century, with marble monuments and iron plots, including the 35-foot Appley memorial at center, commissioned by Mary E. Appley in memory of her family.

Jonathan’s body was never found. But Charles built him a stone.

He placed it in 1849 on the rising ground above Dyberry Creek, in the burying ground that would later become known as Glen Dyberry Cemetery. The Old Methodist Burying Ground beside the early meetinghouse on Church Street had filled quickly, and families were beginning to move their dead to this quieter, more expansive hillside. Newspaper accounts from the mid-1800s described the new cemetery as popular, with plots selling fast and older graves being transferred uphill. It was becoming the town’s chosen resting place even before it was officially dedicated in 1859.

It was here, in this transitional ground between old and new Honesdale, that Charles set his brother’s marker — the place where, in time, their father, Benoni, would be buried, and where generations of Honesdale families have since been laid to rest under marble, granite, and weathered angels.

The inscription is simple:

In memory of

JONATHAN H. SALMON

Second Mate of the Ship Arabella

killed by a whale

Dec. 8, 1847

Aged 28 years

Jonathan never came home. But his name did.

A memorial standing over empty ground is still a kind of anchor. It gives shape to absence. It gives a family a place to stand, a place to say, Here. This is where we remember him, even if the water that holds his body is 2,000 miles away.

The Salmons went on, as families do.

Benoni died in 1851 and lies now in Glen Dyberry, his grave not far from the son whose body never returned. Susan would outlive him. The sisters married, moved, died, some traveling as far west as Kansas, others staying close.

James lived well into the new century, an engineer on the Erie Railroad and, by some accounts, the father of nine. Records show him in 1883 at 30 Munsell St. in Binghamton, New York — a man whose life, on paper, appears steady and prosperous. The railroad offered him work and routine, its dangers more predictable than those of the sea. But the Arabella stayed with him, and he told the story of his brother’s death again and again as the years went on.

Charles’ life followed the rails as well. After the years as tinsmith and merchant in Honesdale, he spent decades in railroading, at one point running the “Steamboat Express” between Elmira and New York. Newspapers later called him “one of the oldest and best-known conductors” on the Erie. He served a term as president of the town council in Susquehanna Depot. He would briefly return to the stove and tinware business in Honesdale as part of Salmon & Delezenne, then go back to the railroad once more — almost as if the movement itself had become his home.

He and Nettie had five children: James E., Mary Louise, Fred R., Clarence E., and Henry Scott. Their daughter Mary married Charles W. St. John Jr., a newspaperman who edited the Port Jervis Daily Union and later ran hotels in North Carolina. Their son Fred, my great-great-grandfather, would work with his brother-in-law at the Port Jervis paper. H. Scott Salmon was a longtime bank cashier in Honesdale. Their descendants would scatter again, to Southern Pines and Hendersonville and elsewhere, carrying with them pieces of a story most probably never heard in full.

Nettie herself — born in Vermont, raised in Tunkhannock and Carbondale, a teacher before her marriage — lived a life that moved with Charles’ career: Honesdale, Susquehanna, Paterson, Port Jervis. Her obituary describes four years of slow decline after “the grippe,” her nervous system gradually breaking down. She was, the paper said, “greatly beloved” and a member of the Presbyterian church since girlhood. She outlived the brother-in-law she never met by more than 40 years.

On the surface, these lives look like ordinary 19th century biographies: births, marriages, moves, illnesses, civic offices held, businesses opened and closed, church memberships maintained. The usual arc.

But somewhere inside each of those arcs was the fact that, in 1847, a brother left and did not come home.

Family history is fragile. Stones weather. Ink fades. Even memory, which feels so permanent, shifts around the edges.

But this story — Jonathan Horton Salmon’s story — survived because someone held onto it each time it was in danger of slipping away.

Hodgdon, doing his job, wrote it in the logbook. Then he wrote it again in a letter. An editor printed it. Charles had it carved. Descendants repeated it — sometimes accurately, sometimes not — but always with wonder: We had an ancestor who was killed by a whale.

Later, archives and museums stepped in. The logbook that recorded Jonathan’s death sailed back to Sag Harbor, lived for a time at the Kendall Whaling Museum in Sharon, Massachusetts, and now resides in a collection where, if you ask, someone will bring it out, open it to the right page, and let you see for yourself the sentence that changed a family.

Stories outlast bodies. Sometimes they outlast even the places where the bodies were supposed to lie.

When I read the documents now — the logbook entry, the letter, the newspaper story, the inscription in stone — I keep coming back to the same idea: The stories families save are rarely the ones they plan to save.

Life is full of quieter triumphs and losses that never make the papers. Yet this one — this strange, brutal, oceanic death — survived. It passed from a South Atlantic latitude to a small Pennsylvania town, from there into a cemetery on a hill, from there into memoirs and genealogies and late-night searches through records, and finally into this page.

A 19th century whaleman might have called it chance. A minister might have called it providence. A historian might call it archival luck. I think of it as a kind of current.

More than 175 years after a right whale struck a small-boat officer in the South Atlantic, a ripple of that moment still reaches us. A disturbance in the water that says, A life passed here once. Remember it.

If you follow that ripple back far enough — through rivers and railroads and towns and names — you arrive again at an August morning in Sag Harbor, at two brothers from Honesdale stepping aboard a ship bound for oceans they had never seen, at a logbook waiting for ink, at a birthday that will be the last.

And that is where this story, and so many others, begin.